the bench sequencing part 2

by J. Phoenix ~ Images captures from Propellerhead's Reason ~ Hello again! Some of you may have noticed my absence last month. Despite my last article's promise of moving on to Synthesis, that series within this series has been difficult to complete. Synthesis is such a wide ranging subject, involving not only musical ideas, but also physics and mathematics that it is taking far longer to finish than I originally thought it was.

There are many different ways to sequence a pattern as we have seen from my previous article on sequencing. In this article, I'll try to dig deeper into sequencing rhythms having demonstrated some of the lay-outs for different types of sequencers. This article will focus on tips on sequencing basic patterns for beginners; for anyone out there who's already past this point, please bear with me. Soon we will be getting into intermediate techniques in production in this series. Again, we will be using screen shots from Propellerhead's software, Reason, to demonstrate.

In general there are three ways to sequence a pattern of notes or a rhythm loop: step-sequencing, which is done measure by measure and beat by beat, sequencing by recording notes played on a keyboard or pads, and sequencing using a 16-step sequencer.

The first two ways to sequence that we will discuss in this article are recording yourself playing the notes that will be sequenced and step recording. To assist with both of these options, a brief discussion of music theory about duration of notes is necessary. 16 step sequencers use the same applications of music theory, but they visually simplify the duration of notes. In recording or step recording this visual simplification isn't present.

In music, all notes each have their own specified duration. There are many different types of notes, each being a different way of designating how long a note lasts. The first thing to define a note's duration is the time signature of the piece. While there is electronic music that is in altered time signatures, just like most traditional music, most electronic music is usually in 4/4 time. This means each measure or bar = four quarter notes, and the beat is on the quarter notes. To demonstrate a contrast, 2/4 time means that each measure or bar has 2 quarter notes, and the beat is still on the quarter notes.

In 4/4 time, the divisions equate something like this:

A whole note = one note that lasts four quarter notes time, or an entire measure in 4/4 time. (1 whole note per measure)

A half note = one note that lasts two quarter notes time, or a half a measure in 4/4 time. (2 half notes per measure)

A quarter note = two eighth notes time, or one quarter of a measure in 4/4 time. (4 quarter notes per measure)

An eighth note = two sixteen notes, or one eighth of a measure in 4/4 time. (8 eighth notes per measure)

A sixteen note = two 32nd notes, or one sixteenth of a measure in 4/4 time. (16 sixteenth notes per measure)

A 32nd note = two 64th notes, or one thirty-secondth of a measure in 4/4 time (32 32nd notes per measure)

and there are sixty four 64th notes in one measure in 4/4 time.

To put things into perpective again, one quarter note = 16-64th notes

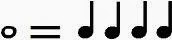

You'll notice that the notes themselves are written in such a way to show their form. A whole note has no line, and is an open circle. A half note is an open circle w/ a line, a quarter note is a closed circle with a line, and an eighth note has a closed circle w/ a line and flag. The flags increase as the divisions get smaller as well, so that a 64th note has four flags.

Now, while in traditional music we rarely see 32nd notes or 64th notes outside of snare rolls or very brief sections of music (they're somewhat difficult to play, especially for long periods of time), in electronic music we do see these notes used somewhat more frequently, because a machine can play them more easily. In addition, these divisions allow for very detailed arrangement of notes because they are so small.

The reason I throw this music theory at you is because knowing the divisions of notes becomes really helpful in relation to recording sequences or in using step-sequencing because of quantization.

Quantization basically "snaps" notes to their specified divisions. In recording this means if you hit a note slightly off from where it should be in the measure, it will snap to the right placement. In step sequencing quantization is used to specify how long a note will play or how long a note will not play.

Step Sequencing

Step sequencing refers to sequencing beat by beat using a numeric system. This is something you'll rarely encounter using software, but frequently encounter when using keyboards and other hardware sequencers, especially in the eighties/late 90's. Step sequencing allows you to select the duration of the note (or rest/silence) beat by beat, measure by measure numerically.

Usually this is displayed in a format like this:

Measure indicates the measure you are working within, beat indicates the beat you are on at the moment, and click designates where in the beat you are. Click goes up to 096. Through quantization you select what note step you'll be creating a note or a rest with. So using this system, to create a four to the floor rhythm you would select quarter notes in quantization, and press the key the thump is on four times. As you do so the numbers will change with each beat played, 001.01.001 to 001.02.001 to 001.03.001 to 001.04.001 and finally ending with 002.01.001 When playing smaller note durations, such as eighth notes or sixteenth notes, you will see where you are at in a beat through looking at the click section.

Learning how to program in step sequence was one of the more difficult things I learned to do, and was the first way I learned how to sequence. It is my least favorite means to sequence with, however, learning it certainly helped me out--and certainly made me appreciate the other types of sequencing that are possible.

Recording Sequences

Recording a sequence can be a useful way to sequence a rhythm in relation to what has already been sequenced by simply playing exactly what you want to hear. It is useful for playing melodies and for sequencing rhythm. Your ability to record sequences if you use software will be dependent on what other equipment you have, such as a midi keyboard, or other midi-equipped gear and your ability to use midi with your software. The good news is that midi equipment to control software programs is becoming increasingly available and cheap to purchase as well. Most hardware since the late 80's has the ability to record played sequences as well.

Recording a sequence can easier than recording audio; the process is quite the same. Most often there is a record button, and the option for quantization should be visible as well. If quantization is enabled, it will snap notes to the closest specified division within the measure. Some sequencer's quantization system will also limit the duration of the notes to the quantization setting, meaning if quantization is set to eighth notes, not only will the played notes snap to eighth note divisions within the measure, but they will also only last an eighth note long. This is important to know, because if you are trying to play a quarter note duration, but want the note to hit on an eighth note in the measure you may run into difficulties.

In recording sequences, you'll be able to specify a loop duration (usually 1 to 4 measures) and be able to repeatedly add more notes to the sequence as it loops. This allows you to hear what you've already played (or what you're recording along with), and you should be able to change your quantiztion settings as well, meaning you can record one part in quarter notes and then switch to sixteenth notes. I find the fact that you can record in a loop format most useful personally.

Another advantage of recording notes in a sequencer vs. recording audio itself is that it is easier to edit than audio, as you will be editing note information itself, and not the sound of the notes. The sound of the notes remains relative to what you assign it to be. In audio recording/editing the sound of the notes is fixed, so to speak.

16 Step Sequencing

We covered what 16-step sequencers look like in my last article on sequencing. Remembering that each of the 16-steps on the sequencer = one 16th note is very helpful; placing a note every four steps will equal four quarter notes, placing a note every two steps will equal eight eighth notes and so on. Because of the visual simplicity of 16 step sequencing, it can sometimes be one of the easiest ways to sequence out a rhythm (it can also make sequencing out a melody quite difficult; there are always disadvantages to any system).

I'd like to quickly demonstrate a few simple progressions in 16 step sequencers for rhythm patterns.

Bass Drum/Thumps

A hallmark in House, Techno, and Trance forms is the "four to the floor" bass kick beat. In 4/4 time this means a kick will happen every quarter note in every measure.

On a sixteen step sequencer this is easily written like so:

Because a beat is played every four 16th notes, the bass kick will come in on the quarter notes.

Some additional patterns I can suggest for bass kicks/thump:

Breakbeats can be sequenced like so:

Break beats by nature are still usually using a 4/4 time signature, but instead of using a four to the floor bass beat, they omit a bass beat or two or rearrange the way the bass hits. Hence the name breakbeat.

Another example of a breakbeat thump pattern:

In the above example, only the first and last thumps fall on the first and fourth beat, the second thump is sitting between the second and third beat.

You may find breakbeat patterns initially difficult to master as a beginner, however with practice and time, it becomes easier. Some people prefer to record themselves playing the patterns in breakbeat or DnB and use that method to sequence, because it can allow you to capture a more human rhythm. There will be more on recording sequences later in this article. Many breakbeat and dnb producers work with recorded loops as the basis for their rhythms, avoiding using a sequencer completely; some of the best however still sequence their own out. It is useful to know how to do both.

Claps, Fingersnaps, Snares

Claps, fingersnaps, and sometimes snare hits usually happen every other beat (quarter note), on the 2nd and 4th beats, and this can be sequenced like so:

For writing breakbeat/DnB snare rolls and patterns, it is useful to note that the primary hits or the most often accented hits are still on the 2's & 4's, as in this example below. There is a snare roll involved, and you may notice the roll carries over at the beginning of the pattern if this is looped. Another tip for people writing snare hits for breaks and dnb: usually, you will want to deal with a two-measure progression, with your emphasis roll in the snare coming in the 2nd measure. The below example would actually be the 2nd measure of such a pattern. To keep your snares from sounding too robotic or stiff, use "accent"/velocity changes, or volume changes in the pattern to create dynamics in the snare. This will keep it from sounding inhuman. In the below example, you will notice there are three different colors on the sequenced hits. In Reason's Redrum sequencer you can select 3 different accents or velocities, Red being Hard, Orange being Medium, and Yellow being Soft. This makes for dynamic changes in volume in the pattern. You may notice I kept the hardest accents on the 2's & 4's.

Sometimes the hits are laid down differently, adding a beat, &/or omitting a beat. Frequently breakbeat will employ a laid back snare hit before the hit on the 4th beat. In this example, I've omitted the hit on the 4th beat, but I am still implying the emphasis on the 4th by placing 2 snare hits around it. This causes a syncopation as well.

Toms/Percussion

Programming toms or percussion comes down to a matter of taste, of course. This makes it difficult to suggest anything in this area.

Personally I tend to write one of two types of patterns in toms, either very spare tom hits:

or very complex patterns, involving many 16th notes in a pattern. Again, the same suggestion of changing dynamics comes into play for adding variance to a pattern.

I can say that I find frequently in writing tom patterns that less is often more...that the less notes I sequence or the further I spread them out makes for a better sound. However, sometimes I seek more density in the programming, and in cases like that, I tend to take one tom sound and program it with a lot of complexity. Paying careful attention to the syncopation of a pattern, and to the rests (or silences) in a pattern are important tips for you as well. Remember that rests are the breathing time, and these silences can create a groove of their own. Writing conga/bongo parts work just like sequencing tom patterns. Remember that with both toms and percussion the pitches of the different toms/bongos/congos are important to keep in mind, because frequently these rhythms become their own melodies within the composition.

Hi Hats/Cymbals

Creating good hi hats is always a sticky point for me, unlike Toms/Percussion which seems to come easily. I always want to make it sound like something a human could play or would play...but I also hear the really pleasing results from people that don't even pay attention to how human a pattern may be. Because I don't feel I do well yet on sequencing hi-hats, I'm only going to offer one helpful hint in this area. The common open hihat hits you always hear after the thump (again, common to house, techno, and trance) can be sequenced thus:

The open hi hat is placed on every third step, causing the Tsh you hear in "Boom Tsh Boom Tsh Boom Tsh Boom Tsh" when this pattern is combined with a bass kick.

Of course, there are more things that can be sequenced that I am not going to cover here, such as ride cymbals, shakers, and other percussion parts.

One last mention before I go: frequently you will have a "Swing" option on your sequencing system or software. "Swing" is a system which attempts to make sequenced patterns more human sounding by "swinging" notes slightly out of being dead on accurate, playing the notes very slightly early or slightly late. Because the notes don't hit with exact accuracy, they can sound less robotic, and may present more groove into a pattern. How far away from dead-on accuracy the Swing in a pattern will be is controlled by the amount of swing specified. Just to reassure you, Swing will not throw a pattern out of rhythm if it is applied; the variance it causes is very slight. Some systems using Swing are extremely detailed, allowing you to control what note divisions themselves will swing and by how far. House makes frequent use of this feature, especially in hi-hat patterns.

The best general suggestion I can make for sequencing rhythm patterns is simply to keep yourself organized, start with one sound and move to the next, making sure everything sounds good together bit by bit.

There are many different ways to sequence a pattern as we have seen from my previous article on sequencing. In this article, I'll try to dig deeper into sequencing rhythms having demonstrated some of the lay-outs for different types of sequencers. This article will focus on tips on sequencing basic patterns for beginners; for anyone out there who's already past this point, please bear with me. Soon we will be getting into intermediate techniques in production in this series. Again, we will be using screen shots from Propellerhead's software, Reason, to demonstrate.

In general there are three ways to sequence a pattern of notes or a rhythm loop: step-sequencing, which is done measure by measure and beat by beat, sequencing by recording notes played on a keyboard or pads, and sequencing using a 16-step sequencer.

The first two ways to sequence that we will discuss in this article are recording yourself playing the notes that will be sequenced and step recording. To assist with both of these options, a brief discussion of music theory about duration of notes is necessary. 16 step sequencers use the same applications of music theory, but they visually simplify the duration of notes. In recording or step recording this visual simplification isn't present.

In music, all notes each have their own specified duration. There are many different types of notes, each being a different way of designating how long a note lasts. The first thing to define a note's duration is the time signature of the piece. While there is electronic music that is in altered time signatures, just like most traditional music, most electronic music is usually in 4/4 time. This means each measure or bar = four quarter notes, and the beat is on the quarter notes. To demonstrate a contrast, 2/4 time means that each measure or bar has 2 quarter notes, and the beat is still on the quarter notes.

In 4/4 time, the divisions equate something like this:

A whole note = one note that lasts four quarter notes time, or an entire measure in 4/4 time. (1 whole note per measure)

A half note = one note that lasts two quarter notes time, or a half a measure in 4/4 time. (2 half notes per measure)

A quarter note = two eighth notes time, or one quarter of a measure in 4/4 time. (4 quarter notes per measure)

An eighth note = two sixteen notes, or one eighth of a measure in 4/4 time. (8 eighth notes per measure)

A sixteen note = two 32nd notes, or one sixteenth of a measure in 4/4 time. (16 sixteenth notes per measure)

A 32nd note = two 64th notes, or one thirty-secondth of a measure in 4/4 time (32 32nd notes per measure)

and there are sixty four 64th notes in one measure in 4/4 time.

To put things into perpective again, one quarter note = 16-64th notes

You'll notice that the notes themselves are written in such a way to show their form. A whole note has no line, and is an open circle. A half note is an open circle w/ a line, a quarter note is a closed circle with a line, and an eighth note has a closed circle w/ a line and flag. The flags increase as the divisions get smaller as well, so that a 64th note has four flags.

Now, while in traditional music we rarely see 32nd notes or 64th notes outside of snare rolls or very brief sections of music (they're somewhat difficult to play, especially for long periods of time), in electronic music we do see these notes used somewhat more frequently, because a machine can play them more easily. In addition, these divisions allow for very detailed arrangement of notes because they are so small.

The reason I throw this music theory at you is because knowing the divisions of notes becomes really helpful in relation to recording sequences or in using step-sequencing because of quantization.

Quantization basically "snaps" notes to their specified divisions. In recording this means if you hit a note slightly off from where it should be in the measure, it will snap to the right placement. In step sequencing quantization is used to specify how long a note will play or how long a note will not play.

Step Sequencing

Step sequencing refers to sequencing beat by beat using a numeric system. This is something you'll rarely encounter using software, but frequently encounter when using keyboards and other hardware sequencers, especially in the eighties/late 90's. Step sequencing allows you to select the duration of the note (or rest/silence) beat by beat, measure by measure numerically.

Usually this is displayed in a format like this:

Measure indicates the measure you are working within, beat indicates the beat you are on at the moment, and click designates where in the beat you are. Click goes up to 096. Through quantization you select what note step you'll be creating a note or a rest with. So using this system, to create a four to the floor rhythm you would select quarter notes in quantization, and press the key the thump is on four times. As you do so the numbers will change with each beat played, 001.01.001 to 001.02.001 to 001.03.001 to 001.04.001 and finally ending with 002.01.001 When playing smaller note durations, such as eighth notes or sixteenth notes, you will see where you are at in a beat through looking at the click section.

Learning how to program in step sequence was one of the more difficult things I learned to do, and was the first way I learned how to sequence. It is my least favorite means to sequence with, however, learning it certainly helped me out--and certainly made me appreciate the other types of sequencing that are possible.

Recording Sequences

Recording a sequence can be a useful way to sequence a rhythm in relation to what has already been sequenced by simply playing exactly what you want to hear. It is useful for playing melodies and for sequencing rhythm. Your ability to record sequences if you use software will be dependent on what other equipment you have, such as a midi keyboard, or other midi-equipped gear and your ability to use midi with your software. The good news is that midi equipment to control software programs is becoming increasingly available and cheap to purchase as well. Most hardware since the late 80's has the ability to record played sequences as well.

Recording a sequence can easier than recording audio; the process is quite the same. Most often there is a record button, and the option for quantization should be visible as well. If quantization is enabled, it will snap notes to the closest specified division within the measure. Some sequencer's quantization system will also limit the duration of the notes to the quantization setting, meaning if quantization is set to eighth notes, not only will the played notes snap to eighth note divisions within the measure, but they will also only last an eighth note long. This is important to know, because if you are trying to play a quarter note duration, but want the note to hit on an eighth note in the measure you may run into difficulties.

In recording sequences, you'll be able to specify a loop duration (usually 1 to 4 measures) and be able to repeatedly add more notes to the sequence as it loops. This allows you to hear what you've already played (or what you're recording along with), and you should be able to change your quantiztion settings as well, meaning you can record one part in quarter notes and then switch to sixteenth notes. I find the fact that you can record in a loop format most useful personally.

Another advantage of recording notes in a sequencer vs. recording audio itself is that it is easier to edit than audio, as you will be editing note information itself, and not the sound of the notes. The sound of the notes remains relative to what you assign it to be. In audio recording/editing the sound of the notes is fixed, so to speak.

16 Step Sequencing

We covered what 16-step sequencers look like in my last article on sequencing. Remembering that each of the 16-steps on the sequencer = one 16th note is very helpful; placing a note every four steps will equal four quarter notes, placing a note every two steps will equal eight eighth notes and so on. Because of the visual simplicity of 16 step sequencing, it can sometimes be one of the easiest ways to sequence out a rhythm (it can also make sequencing out a melody quite difficult; there are always disadvantages to any system).

I'd like to quickly demonstrate a few simple progressions in 16 step sequencers for rhythm patterns.

Bass Drum/Thumps

A hallmark in House, Techno, and Trance forms is the "four to the floor" bass kick beat. In 4/4 time this means a kick will happen every quarter note in every measure.

On a sixteen step sequencer this is easily written like so:

Because a beat is played every four 16th notes, the bass kick will come in on the quarter notes.

Some additional patterns I can suggest for bass kicks/thump:

Breakbeats can be sequenced like so:

Break beats by nature are still usually using a 4/4 time signature, but instead of using a four to the floor bass beat, they omit a bass beat or two or rearrange the way the bass hits. Hence the name breakbeat.

Another example of a breakbeat thump pattern:

In the above example, only the first and last thumps fall on the first and fourth beat, the second thump is sitting between the second and third beat.

You may find breakbeat patterns initially difficult to master as a beginner, however with practice and time, it becomes easier. Some people prefer to record themselves playing the patterns in breakbeat or DnB and use that method to sequence, because it can allow you to capture a more human rhythm. There will be more on recording sequences later in this article. Many breakbeat and dnb producers work with recorded loops as the basis for their rhythms, avoiding using a sequencer completely; some of the best however still sequence their own out. It is useful to know how to do both.

Claps, Fingersnaps, Snares

Claps, fingersnaps, and sometimes snare hits usually happen every other beat (quarter note), on the 2nd and 4th beats, and this can be sequenced like so:

For writing breakbeat/DnB snare rolls and patterns, it is useful to note that the primary hits or the most often accented hits are still on the 2's & 4's, as in this example below. There is a snare roll involved, and you may notice the roll carries over at the beginning of the pattern if this is looped. Another tip for people writing snare hits for breaks and dnb: usually, you will want to deal with a two-measure progression, with your emphasis roll in the snare coming in the 2nd measure. The below example would actually be the 2nd measure of such a pattern. To keep your snares from sounding too robotic or stiff, use "accent"/velocity changes, or volume changes in the pattern to create dynamics in the snare. This will keep it from sounding inhuman. In the below example, you will notice there are three different colors on the sequenced hits. In Reason's Redrum sequencer you can select 3 different accents or velocities, Red being Hard, Orange being Medium, and Yellow being Soft. This makes for dynamic changes in volume in the pattern. You may notice I kept the hardest accents on the 2's & 4's.

Sometimes the hits are laid down differently, adding a beat, &/or omitting a beat. Frequently breakbeat will employ a laid back snare hit before the hit on the 4th beat. In this example, I've omitted the hit on the 4th beat, but I am still implying the emphasis on the 4th by placing 2 snare hits around it. This causes a syncopation as well.

Toms/Percussion

Programming toms or percussion comes down to a matter of taste, of course. This makes it difficult to suggest anything in this area.

Personally I tend to write one of two types of patterns in toms, either very spare tom hits:

or very complex patterns, involving many 16th notes in a pattern. Again, the same suggestion of changing dynamics comes into play for adding variance to a pattern.

I can say that I find frequently in writing tom patterns that less is often more...that the less notes I sequence or the further I spread them out makes for a better sound. However, sometimes I seek more density in the programming, and in cases like that, I tend to take one tom sound and program it with a lot of complexity. Paying careful attention to the syncopation of a pattern, and to the rests (or silences) in a pattern are important tips for you as well. Remember that rests are the breathing time, and these silences can create a groove of their own. Writing conga/bongo parts work just like sequencing tom patterns. Remember that with both toms and percussion the pitches of the different toms/bongos/congos are important to keep in mind, because frequently these rhythms become their own melodies within the composition.

Hi Hats/Cymbals

Creating good hi hats is always a sticky point for me, unlike Toms/Percussion which seems to come easily. I always want to make it sound like something a human could play or would play...but I also hear the really pleasing results from people that don't even pay attention to how human a pattern may be. Because I don't feel I do well yet on sequencing hi-hats, I'm only going to offer one helpful hint in this area. The common open hihat hits you always hear after the thump (again, common to house, techno, and trance) can be sequenced thus:

The open hi hat is placed on every third step, causing the Tsh you hear in "Boom Tsh Boom Tsh Boom Tsh Boom Tsh" when this pattern is combined with a bass kick.

Of course, there are more things that can be sequenced that I am not going to cover here, such as ride cymbals, shakers, and other percussion parts.

One last mention before I go: frequently you will have a "Swing" option on your sequencing system or software. "Swing" is a system which attempts to make sequenced patterns more human sounding by "swinging" notes slightly out of being dead on accurate, playing the notes very slightly early or slightly late. Because the notes don't hit with exact accuracy, they can sound less robotic, and may present more groove into a pattern. How far away from dead-on accuracy the Swing in a pattern will be is controlled by the amount of swing specified. Just to reassure you, Swing will not throw a pattern out of rhythm if it is applied; the variance it causes is very slight. Some systems using Swing are extremely detailed, allowing you to control what note divisions themselves will swing and by how far. House makes frequent use of this feature, especially in hi-hat patterns.

The best general suggestion I can make for sequencing rhythm patterns is simply to keep yourself organized, start with one sound and move to the next, making sure everything sounds good together bit by bit.

Comments

Post a Comment